Updated April 2024

"What does love look like? It has the hands to help others. It has the feet to hasten to the poor and needy. It has eyes to see misery and want. It has the ears to hear the sighs and sorrows of men. That is what love looks like."

—Saint Augustine

Looking at portraits carefully can provide a way for the viewer to perceive and feel unencumbered, participating in part with another's life. On our own we might not be interested in encountering another’s path. Studying photographs of people not the same as you or me, privately and personally can reveal much about ourselves, our relationships and behaviors practiced in this life. When focused, our conscious and unconscious views can open unguarded, beckoning and inviting us to examine our learned assumptions and predetermined mind sets. With empathy and compassion, we can see another's portrait more clearly, finding acceptance, kindness and common essential forms leading to rock-solid relationships, respecting those different from ourselves.

Shelby Lee Adams

Painter – Ivan Albright

“Do I want to paint the boundaries of a face or do I want to paint what wisdom the face can contain-a face that looks at a thousand years as if they were a second. A face that goes to the eternal force of life and has found it.” He knew he wanted to express something else. “I want a face that has been compassionate. A face that has shed tears …That has been alive with joy … that opens the door to you. A face that has faith-a wrinkled face, an old face, a face ready for death.”

Ivan Albright

To become familiar is to change your perspective.

To change your perspective is to actually know another.

When you acknowledge and participate with others often your heart opens to them, but they also unlock themselves to you.

To openly interconnect and learn to appreciate each other is the best way to stop aversions, stereotyping and prejudice for all races and cultures.

To see ourselves on common ground is to live more peacefully.

---Shelby Lee Adams

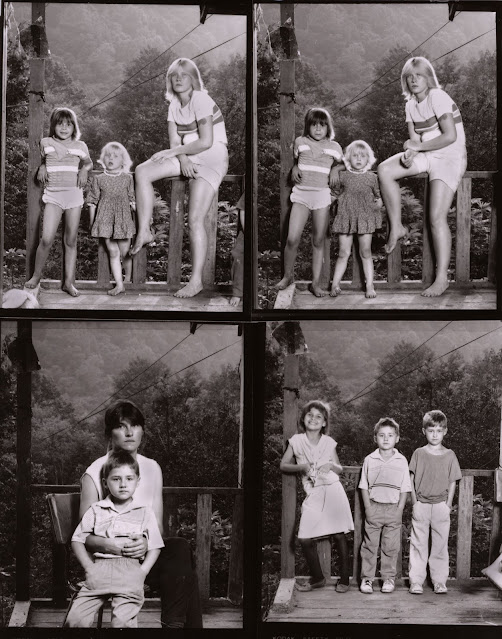

Hermie, 1988

[Bruce and Sally's Mother]

Printed 2021

_____________________________________________________

Bruce

Bruce & Barb [brother and sister] , 1988

Sherman said of his son Bruce now deceased, “My boy he doesn’t know how to let go of anything, he fights too easy. One time when he and his girlfriend were having trouble, he took off in his car driving country roads over 100 miles an hour, lookin' for her, he rolled his car three times in a curve and nearly killed his self, chasing after a girl. I guess she told him he was not good enough and that set him off. He hit his head, and He was never quite right again, he was at the University hospital for over 3 months with brain trauma. After he got out of the hospital many of his friends and kin too, looked away and treated him differently. He was different and stayed at home mostly after that accident, then one day it was really hot, and he was sitting up in the 3rd floor window smoking and he just pitched over and fell 3 floors onto pavement and died.”

—Sherman Jacobs

"When our children go into the cities for work or are drafted into the army, they are forced to deny their heritage, change their way of talking, and pretend to be someone else, or be made to feel ashamed, when they really have something to be proud of."

Verna Mae Slone

What My Heart Wants to Tell

Pippa Passes

“The mountaineer would like to have just one person—one day—come into his hollow and show some sign of approval of the way he has lived over the decades, and the way he wants to live forever. And not try to change him without first knowing him.”

John Fetterman

Stinking Creek

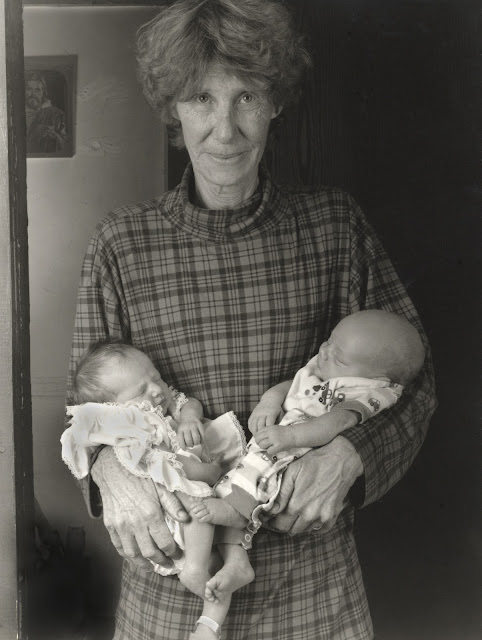

Shirley and Son, 2007

The engagement and involvement that drives and informs the making of an original photograph is often not written about, at least I have never attempted such writing. When I say, “the making,” that is how I describe the elements involved. In the photograph, Shirley and her son Billy Ray are people I know living in Leatherwood, Kentucky. Shirley has known me and my photography through her sister Goldie May. Since 1989, I have photographed with her father Pearl, neighbors, her sister and brothers. How and who introduces you to a family is important if you wish to gain trust and have that reflect in your photographs. Even better, repeated visits over time establish a more informed understanding and that contributes to more engaged pictures.

In the environment here I was impressed with the front porch, all the different horizontal and vertical lines converging together made a visually interesting lived-in display. This house was built in the 1930’s and was a coal mining company house that miners stayed in when working. The house is still owned by the Kentucky River Coal Co. and now rented cheaply. Very few authentic mining camp houses are still standing and occupied. I felt instinctively this environment was important to photograph and Shirley a genuine and natural subject. Seeing this place for the first time as important motivated me to want to photograph.

Working with a 4 x 5 view camera with adjustable swings and tilts I could visually align the center porch post using the camera levels and grided ground glass. With this camera, I am able to adjust and align the building’s perspective, centering and balancing most elements of the house to appear straight. Of course, this building was constructed on a hill side that had begun to sag and shift in parts over time, so some sections do not line up perfectly, adding to the character of the building.

The house stood in the shade and dark side of the mountain. To create an arresting image, I felt I needed to introduce some artificial lighting. Often my subjects ask to be photographed in areas where the light is not always agreeable to film exposures, so since 1980 I have practiced mixing artificial light with daylight, achieving hopefully better overall compositions in diverse lighting situations. The one thing I ask Shirley to move was some laundry hanging from a line on the front porch. This was the place I thought she would look natural standing. As it turns out, she said, she stood and sat in that corner of the porch often. Her son and I moved my lights and equipment from the trunk of my car, and he helped me set up my light stands and find AC plug ins in the house.

I set up my strobe lights outside visualizing the overall composition and later adding a battery-operated strobe light on the inside floor lighting the ceiling and backlighting Billy Rae. I asked Shirley's son to lean in the doorway looking straight at the camera. I knew his position would add to the composition and help balance the overall photograph. Shirley posed herself holding a cigarette in her right hand. After, making two or three Polaroids which take only 30 seconds each to develop we reviewed the Polaroids together. We had made 4 exposures on film and then studied the Polaroids. The pattern of light and shadows on the wall above Shirley’s head was distracting, too harsh and disruptive. Shirley looking at the Polaroids said she wanted to pull her hair back and freshen up a bit. Shirley’s son hardly moved and was fine with his image throughout the process.

While Shirley was getting ready, I placed an umbrella in a strobe light head on the right side of the composition and moved the light more to the front to gently light Shirley. When Shirley returned, she fumbled with her hands a bit and ended up folding one hand over the other, placing them on the porch rail. When everything seemed ready, I ask Shirley to remember and think of her father Pearl who had died a few years before, while also looking directly into the camera. In our culture families are close and I’ve learned different ways to get subjects to relax before the camera. The suggestion of family thoughts and memories often calms and relaxes a subject while being photographed. We then exposed 4 more negatives and made two or three more Polaroids. When we reviewed these last Polaroids, we all liked the photograph we had just made. It is standard practice for me to leave 2 or 3 Polaroids with any family I photograph returning with prints the next visit, even if it is 6 months later.

Each visit and photo session varies somewhat from place to place. The timing of each visit can vary from 2 to 3 hours to ½ a day. Sometimes we talk for an hour or two before photographing or taking a break in the middle of a session and just get to know each other better. On occasion, I visit having no ideas or feelings to photograph and just relax and enjoy the visit. There are families I’ve known for over 30 years and I continue to visit and photograph. Some have their own ideas’ and places they may want to be photographed. Most important, I always ask, do you want to be photographed, because it requires a commitment of time and energy and most always-everyone wants their picture made. It’s the only way I work. Regardless, I call my work collaborative, and grounded in real relationships.

Unfortunately, I gave away or lost all the Polaroids we made that day of Shirley and Billy Ray. When I returned to give Shirley 8 x 10-inch photos the next year, I asked if I could photograph her again, she agreed. This time we photographed in her kitchen and below is a Polaroid I kept for myself.

From an interpretation of Will Faulkner’s famous story, Barn Burning

Faulkner seems to suggest that human understanding and perception are unstable and always changing, subject to the environment and other people. His writing style also suggests a lack of clear resolution to the action. For example, at the end of his story “Barn Burning,” Faulkner’s fiction intends to reflect the struggles faced in the everyday world—struggles that usually don’t have clear resolutions. In Faulkner powerlessness and the quest for power and self-expression are expressed through Barn Burnings.

Quote from Faulkner's text, The Hamlet: "Ain't none of you folks out there done nothing about it?" he said.

"What could we do?" Tull said. "It aint right. But it ain't none of our business."

"I believe I would think of something if I lived there." Ratliff said.

—Will Faulkner

The Hamlet

In the mountains when someone opens their door to you, they often open their hearts to you forever. This is part of the drawing power of the region and its people, that makes my photography and friendships there an Eternal Returning. That drawing power is something extraordinary and accessible to those willing to make the journey.

—Shelby Lee Adams

Dan Napier’s Funeral – 1991-Text

When growing up in the mountains, I often enjoyed staying with my grandparents whose religion was The Old Regular Baptist. They had long services that started at 9:00 AM and went till noon, sometimes followed by what they called, “Dinner on the Ground.” Some called this an outdoor supper. My aunt Cuna Mae often drove us to the different country churches for Sunday meet in’s. She owned and drove a four-door green Bel Air Chevrolet and I usually got to sit up front with her as she chauffeured us around.

When their church has a funeral, it often is a three-day affair. Usually, the corpse is first taken to the local funeral home and prepared to be viewed in a coffin, the deceased is then often taken back to the home for an all-night or two vigil. In this Napier’s Funeral, all the services were held in the local funeral home. A wake in our mountains is often held to give relatives and friends time to visit their kin one more time. Sometimes folks drive great distances, coming from out of state where they work. Before burial, relatives can mourn, sing hymns together and pray for the deceased privately beside the coffin and with a preacher if desired. People usually bring food and serve coffee, bringing flowers and other necessities the family might use. On the third day the coffin is taken to a local church where there is a service and then the coffin is taken to a local cemetery or buried in a family plot near home.

A wake can be an informal affair, personal and emotional. I’ve seen miners who just got off their work shift at the mines come directly to a wake in coal dust covering their cloths and faces to mourn and pay their last respects. Mothers pick up their little children and carry them to a coffin to say goodbye to grandma, for example, sometimes even allowing the child to touch the hand of their relative, saying goodbye. I've seen grown men with tears in their eyes walk up to a coffin and place photos of their children in the coffin to be with the deceased, as they believe this custom with photographs goes with the relative to the beyond. As a photographer with a lot of equipment, tripod, lights, stands and umbrella’s one has to be quite and select the right times to make photos.

So, photographing at a funeral from my culture used to be a ritual, not so much practiced anymore. At the Napier’s Funeral we see three generations of the family photographed. I probably made 20 4x5 Polaroids that night, giving most to different relatives and neighbors. I also exposed 16 4x5 film exposures to print and give to the family later. This I consider part of my community service work. Later, I selected one negative of the father with his deceased son making a horizontal composition, with his permission, later publishing in my first book.

SLA

“What was your experience taking these pictures?’’

My uncle Doc Adams used to ride a horse into the community of Leatherwood, for one day each week. This was after World War II, he provided health care for the coal miners and their families, he was employed by the coal company called The Blue Diamond. He set up his clinic in a vacant coal mining office, established just for his use. There were lots of services he provided for the rest of the community who had no doctor. Dalton in the far left of the men’s photo was a patient of my uncle. Dalton had some disabling injuries from working in the mines, my uncle treated and helped him get a deserved disability.

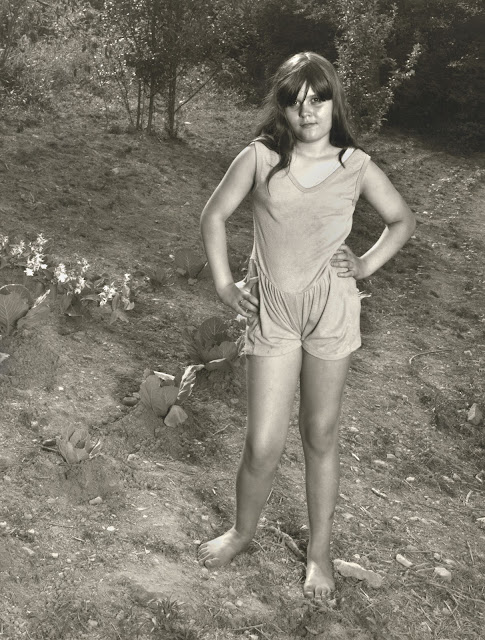

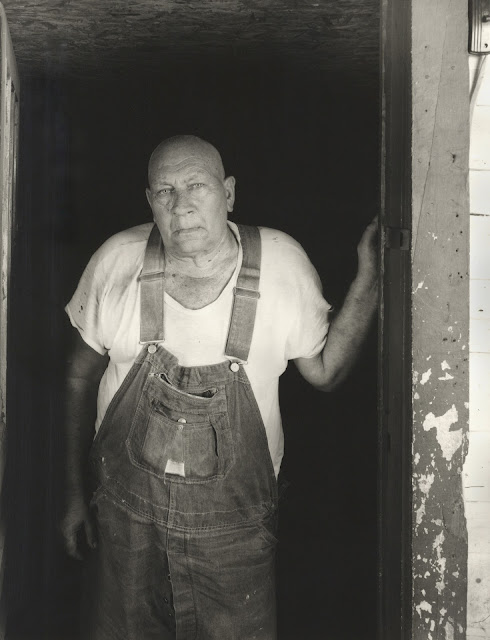

In the 1980’s I began photographing in the Leatherwood community, a rural area with one country store with one gas pump. The post office was a small two room building with a flagpole in the front yard. Slemp was the name of the office with its own zip code, 41763. From there to the county seat of Hazard is 18 miles. Dalton and I were introduced by a friend, a serpent handling preacher we both knew. My uncle’s name came up in conversation. The fact that I was Doc Adams’s nephew opened Dalton and his family to me. They looked at my photographs made in their community that I always kept in my car when visiting. This was before my first book was published, which made showing my work easier. Dalton and his family liked my photographs and wanted to be photographed.

In the fall of 1989 when in Kentucky, I had called Dalton and made arrangements to visit and photograph him with his entire family. I had photographed some of the family before, but no photo excelled from previous sessions. It was a beautiful day in late October, this visit. Dalton had four children, three daughters and one son, all mid-thirties in age. His wife had passed several years before. No one wanted to go first, after I set up my 4x5 camera and lights. The women were shy, giggling and laughing to themselves.

Dalton said, “Well boys lets go first, that will put the girls at ease.”

Two of the men to be photographed were Dalton’s son in laws. We did several photos of the men standing together with Dalton’s son Bob on the ground in front of the porch. I made Polaroids to show everyone and left copies. The three women seemed to like the Polaroids, but were still skittish. I felt some tensions between the youngest couple. An hour had pasted, I knew the light was changing. I suggested to the women we make their photos in the same way and place without moving the camera and they seemed to like the idea. The woman nick named Hawk was the first to move forward, we made several 4 x 5 exposures with Polaroids, just with the women. None of us had the idea of pairing the images together when we made the pictures. That came to me when developing and proofing film in the darkroom.

—Shelby Lee Adams